What Is Making Our Deficit So High Again

Introduction

For decades, a consensus of economic policy experts warned that escalating national debt brings about higher involvement rates, larger government interest costs, and slower economic growth. For the virtually role, politicians and voters at least gave lip service to these concerns. Today, the return of trillion-dollar annual budget deficits—projected for this year and heading toward $2 trillion within a decade—is being greeted with a collective shrug.[1] Indeed, a variety of spending proposals over the past several months exhibit a political momentum for increasing deficits fifty-fifty further. If enacted, such proposals risk a fiscal crisis, fifty-fifty if involvement rates remain relatively low.

The public's general indifference toward rising deficits may reflect the experience of the recent by. The Great Recession—plus the resulting stimulus laws and financial bailouts—caused the annual deficit to ascension from $161 billion to more than than $1.4 trillion in simply ii years (2007–09). This sparked Tea Party rallies and helped the Republicans win control of the House of Representatives in the wave election of 2010. Withal the terminate of the recession, expiration of stimulus spending, and repayment of most financial bailout funds (plus some modest spending caps and upper-income tax hikes) reduced the deficit to $439 billion by 2015. This fairly rapid decline may take convinced many Americans that earlier arrears concerns had been overblown. The problem with this inference: upkeep deficits driven past temporary factors such every bit wars or recessions are different in kind and effect from relentlessly increasing deficits driven by entitlement spending, specially Social Security and Medicare. Today the economy is growing, wages are rise, and involvement rates are depression; Americans do not yet experience the economic effects of rising debt. They will.

Yet, some economists and commentators have grown accepting of big upkeep deficits. Jason Furman and Lawrence Summers, for case, have asserted that low interest rates make the national debt more affordable.[two] MIT'south Olivier Blanchard asserts that, as long as the economical growth rate exceeds the interest charge per unit paid on regime debt (r < thou), the debt'southward share of the economy will fall.[3] Commentators Chris Hayes of MSNBC and Matthew Yglesias of Vocalization contend that fifty-fifty larger deficits than the country did experience would have softened the Great Recession and stimulated a strong economy.[iv]

Among others, Furman and Summers also argue that ascent government debt no longer crowds out business investment, adding that "no one seriously argues that the cost of uppercase is property back businesses from investing."[5] Yglesias asserts that new debt can be used on pro-growth projects that outset any economic elevate results from the borrowing.[6] Advocates of Modern Monetary Theory regard whatever concern about deficits and debt as unnecessary—and holding the economic system back from a new era of prosperity.

DOWNLOAD PDF

By contrast, this paper argues that ever-rising deficits and debt, even in a low involvement-rate environment, do pose a pregnant chance to the economy—that is, to Americans' prosperity and living standards. Deficits all the same matter, and the standard economical assumptions about government debt remain in force. Trillions of dollars in new regime deficit spending volition not produce significant new economic growth. Instead, the ascension deficits and debt that are already broiled in to current entitlement spending will export future generations to exorbitant interest payments to fund consumption by senior citizens. Here are the bug with the view that in that location is little to worry about:

Interest Rates and Interest Payments

Consider Blanchard'due south merits that, every bit long as the economic growth rate exceeds the interest rate paid on regime debt (r < 1000), the debt'south share of the economy will fall even if the involvement payments are funded entirely by borrowing.[7] This formula, however, assumes that the debt is growing only from the borrowing cost of those involvement payments—and that the residuum of the budget (excluding involvement spending) is counterbalanced. Otherwise, increased borrowing to pay for the rest of regime will further increase the debt.[8] In other words, the debt's share of the economic system will continue to ascent, not fall.

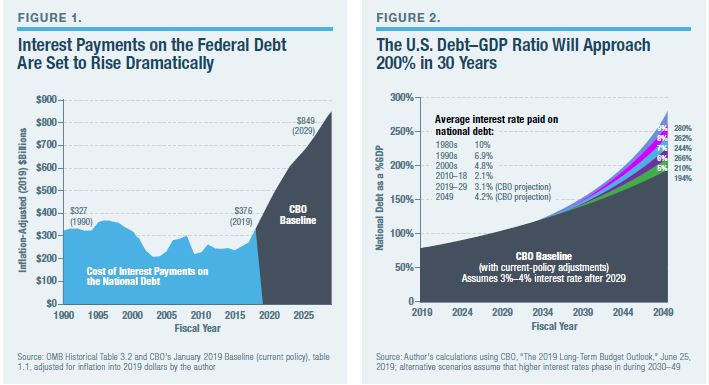

And that is exactly what is happening. The U.S. Treasury borrowed $984 billion in 2019—far exceeding that year's $376 billion interest payments (Figure ane). More than broadly, the electric current-policy upkeep baseline, using Congressional Upkeep Role (CBO) information, shows that government debt—39% of Gdp in 2008—has already doubled, to 78%. The debt-to-Gross domestic product ratio is projected to achieve 105% inside a decade, and 194% afterward 3 decades (Figure two).

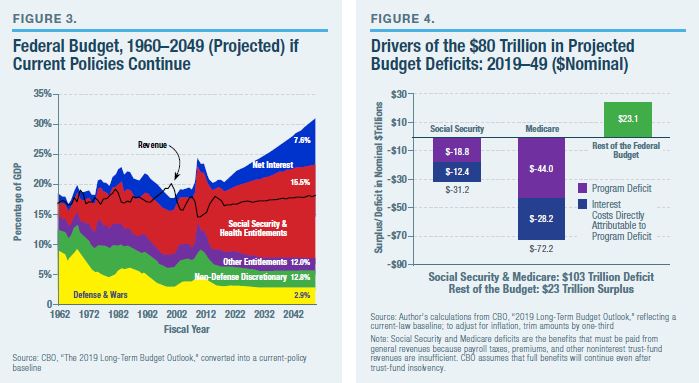

CBO'southward project assumes no wars, no major recessions, and no expensive new federal initiatives.[9] Accordingly, the government's involvement payments on this debt—which take risen from ane.2% to 1.8% of Gdp since 2015—are projected to attain three.4% inside a decade and 7.6% (and steeply rising) past 2049 (Figure iii).

By that bespeak, the interest payments on the national debt would be the federal government'southward largest almanac expenditure, consuming 42% of all projected tax revenues. In fact, but the increase of half-dozen.4% of GDP in interest costs between 2015 and 2049 would exceed the cost of the entire Social Security system, Medicare system, or total discretionary spending budget over that period. So what? Funding this expenditure within existing spending levels would require eliminating more than than one-quarter of all federal program spending. Or, on the taxation side, it would require choosing betwixt options such equally an beyond-the-board income-taxation hike of 19 percentage points or establishing a 38% value-added revenue enhancement.[x]

Calculations based on CBO information prove that these interest costs will drive the annual budget deficit to 7% of GDP within a decade and near 13% after three decades (13% of today's GDP would be the equivalent of running a $iii trillion almanac deficit—dramatically higher than the actual deficit of just under $1 trillion in 2019). And these projections for growing deficits presume peace, prosperity, and low interest rates.

While information technology is tempting to dismiss long-term budget projections as unreliable, the ones presented here are actually optimistic. CBO's projected primary deficits are driven by 74 million baby boomers retiring into Social Security and Medicare, which will bulldoze these systems into a $72 trillion cash deficit (plus $31 trillion in resulting involvement costs) over 30 years (Figure four).[11] This is not a guess; information technology is demography. The baby boomers be, and their program payment formulas are ready in law. Moreover—and apart from Social Security and Medicare—CBO's projections optimistically assume no major recessions or expensive new spending programs. The CBO baseline assumes that defense spending as a share of the economy falls to 1930s levels, and the rest of the non-health-intendance budget also falls every bit a share of the economic system.[12] If any of these optimistic assumptions proves wrong, deficits and interest payments on the debt will rising even higher.

To put this another way: even if Blanchard, Furman, Summers, and others are correct that involvement rates volition likely remain well below the averages of the past 50 years, the rise debt chief will all the same button the debt to nearly 200% of GDP under the most optimistic assumptions. A authorities debt that permanently grows significantly faster than the economy itself is not sustainable.

What Happens if Interest Rates Begin to Spiral

The federal government currently pays an average interest rate of 2.3% on its debt. This is far below the previous average rates of 10.v% (1980s), half-dozen.9% (1990s), and 4.eight% (2000s).[thirteen] CBO assumes that involvement rates paid on the debt will remain historically low—rising to three.four% over the next decade and 4.2% over 30 years.[14]

What if interest rates ascent higher? Each 1-percentage-point increase in the interest rate that the federal regime must pay on the national debt means an additional $1.8 trillion in interest payments over the decade and $eleven trillion over 30 years.[15] To put that in perspective:

- A 1% involvement-charge per unit increase would add nearly as much government debt—$eleven trillion—as the 2017 revenue enhancement cuts, extended over 30 years.[16]

- A two% involvement-charge per unit increase would impose a xxx-year price of $22 trillion, which is greater than the entire Social Security shortfall.[17]

- A three% interest-rate increase would cost $33 trillion, or nigh as much every bit the unabridged defense budget over the next 30 years.[eighteen]

- A return to 1990s interest rates would add $1 trillion to the projected deficit a decade from now, pushing information technology to $3 trillion per year.[nineteen]

The debt-to-Gdp ratio is projected to accomplish 194% of Gdp in thirty years nether current policy. If interest rates were to rise to 6.9%—the average charge per unit paid by the federal government on its debt in the 1990s—the U.Southward. debt-to-Gdp ratio would motion closer to 250%.

Why Involvement Rates Might Rise

In recent years, interest rates have faced downward pressure from the slow growth of the labor force and productivity, a soft-money Federal Reserve, and investor preference for safer avails—factors that may go on to persist. On the flip side, at that place are reasons rates could ascent. Over time, total individual savings may become constrained by baby boomers drawing down their savings or emerging markets attracting an increasing share of global investment. An increase in nominal economic growth rates—whether from productivity, inflation, or even a reversal of the labor-strength slowdown—could also nudge rates dorsum up. A recent report shows that in countries with high private debt—such equally the U.S.—rise government debt puts added pressure on interest rates.[20]

A contempo analysis past old Treasury economist Ernie Tedeschi shows that each pct-point increase in federal debt as a share of Gdp raises the interest charge per unit on the 10-year bond by four basis points—fifty-fifty if other economic factors are currently pushing rates back down.[21] These figures line up with several other academic studies of the by two decades, which estimate that each per centum-betoken rising in the debt-to-GDP ratio pushes up involvement rates by 2 to 4 footing points.[22]

If the interest rates paid by the government remained at 3% forever, the debt-to-Gross domestic product ratio would notwithstanding reach approximately 175% of Gross domestic product over three decades, rather than 194% under baseline involvement rates.[23] However, the bourgeois consensus supposition—that each ane-pct-point increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio raises interest rates by iii footing points—suggests that the coming 116-per centum-betoken increase in the debt-to-GDP ratio should raise interest rates past approximately 3.5 percentage points. Information technology is highly unlikely that offsetting factors belongings involvement rates downward—slower growth of productivity and the labor force, depression aggrandizement, a soft-money Federal Reserve, a global flight to condom investments—could counter the debt-to-GDP ratio effect.

Finally, market psychology is e'er a factor. A sudden, Hellenic republic-similar debt spike—resulting from the normal upkeep baseline growth combined with a deep recession—could crusade investors to see U.S. debt as a less stable asset, leading to a sell-off and an interest-rate fasten. Additionally, rising interest rates would crusade the national debt to further increase (due to higher interest costs), which could, in turn, button rates fifty-fifty higher.

Gambling on Low Interest Rates

Economists such as Furman, Summers, and Blanchard affirm that interest rates will remain permanently below the rates of the past several decades because of factors such every bit depression aggrandizement and slow productivity growth. Nevertheless by economists have more than once prematurely declared a permanent victory over long-term economic challenges. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, Keynesian economists declared that they had fully tamed the business organization cycle—correct before viii barbarous years of rising aggrandizement and interest rates, as well as economical stagnation. Then, in the late 1990s, some journalists and economists explained that the Federal Reserve (with assist from the U.S. Treasury) had finally eliminated the risk of serious recessions through smart budgetary policy and targeted market interventions. Within a decade, low involvement rates and an unforeseen housing bubble brought on the worst economical downturn since the Nifty Low.

This should bring some humility to claims that we no longer need to worry about interest rates. Building the largest regime debt in history on the adventure that involvement rates will remain low forever is imprudent in the extreme. Instead, the U.Southward. should gradually stabilize the national debt equally a share of the economy.

Economic Growth and a Rising National Debt

The dangers of mounting government debt accomplish far beyond the rise federal budget interest costs and their resulting fiscal squeeze. While the U.S. may be awash in capital today, a federal debt headed toward 200% of GDP will reduce the savings bachelor for business organization investment, ultimately reducing productivity and growth. These furnishings would be exacerbated by falling private savings rates, as retired baby boomers volition continue to draw downwardly their IRAs and 401(thou)s to finance their retirement. Some of these savings may be replenished by global investors, although the returns would accumulate outside the U.S., limiting domestic income. As savings rates decline and more of those savings are borrowed past the government, fewer savings are available within the private economy to finance the concern and capital letter investments that ultimately drive much of economic growth. A contempo written report published past the Mercatus Center suggests that swelling debt levels accept already reduced U.S. economic growth rates by up to 1 percent point annually.[24] CBO estimates that the electric current debt trajectory will reduce annual incomes by $7,000 (adjusted for aggrandizement) within three decades, relative to a scenario where the debt remains at 78% of GDP.[25]

Autonomously from interest rates and payments, economists such as Paul Krugman and Stephanie Kelton say that U.S. deficits are economically harmless because they are financed in domestic currency.[26] Information technology is truthful that decision-making the currency certainly makes default unlikely and presents an option for the regime to inflate the debt away. Relying on aggrandizement, however, would substantially harm the economy and raise the toll of future borrowing. Notwithstanding, default or no default, a financial crisis tin can nevertheless occur, every bit investors lose organized religion in the nation's ability to handle a quickly growing debt burden—and terminate ownership U.S. debt or need much higher involvement rates to do then.

Moreover, America's status every bit the globe's largest economy may lower the debt-to-GDP ratio at which a financial crisis could occur. In 2010, Greece warned the European union that it might default. At the time, the country's national debt had reached 175% of its GDP. Greece's $350 billion debt, notwithstanding, represented a pocket-sized share of the global economic system and global savings puddle, leaving it relatively like shooting fish in a barrel for other governments and markets to bail out the country. A U.Southward. debt equal to 200% of its GDP—$100 trillion in total debt by that signal—would stand for a much larger share of the global economy and global savings puddle. Other governments and markets would take much less chapters to rescue the U.S. Instead, an uncontrollable U.S. debt could destabilize the entire global financial organization. While this may seem far-fetched, the projection of a debt approaching 200% of Gross domestic product past 2049 is based on optimistic predictions: that interest rates remain moderately low by historical standards and that the country does not feel additional deep recessions or get embroiled in additional wars. The last decade has shown how deep recessions, in item, tin accelerate debt crises in governments (such as Greece) whose finances had already been delicate.

What About the Benefits of Government Debt?

There are too advocates of more ambitious borrowing, the argument existence that a narrow focus on the economic drag of debt fails to account for the economic benefits of government investments that this debt makes possible.[27] And pocket-size levels of debt tin be pro-growth if they finance productive long-term investments. Unfortunately, that consequence is non relevant to the current increment in arrears spending and debt. Virtually the unabridged projected expansion of the national debt over the next 30 years—116% of Gdp in additional borrowing—will be necessary to comprehend the $103 trillion cash shortfall of the Social Security and Medicare systems (including the interest costs). Essentially, the federal government will borrow from the financial markets non to finance new investments but rather to subsidize the electric current consumption of senior citizens.

In any event, many current spending proposals that would incur new debt are non necessarily pro-growth. Medicare-for-All would mainly finance current consumption. A wide climate agenda of new regulations, taxes, and expenditures, whatever their environmental merits, would likely harm the economy in the short- and medium-term. Whatsoever long-term economic benefits would depend on the evolution and distribution of new technologies that truly reduce global warming without imposing large new economic costs. Forgiving past pupil loans would stand for a transfer payment, not an investment, and "free" public higher would assistance economic growth simply to the extent that college enrollment and completion rates abound significantly plenty that the economic benefits of educational attainment exceed the costs of subsidies to all college students—many of whom would have attended college either fashion. Bernie Sanders's proposed guarantee of a $xv-per-hour authorities task for anyone who wants it would reduce productivity growth by moving workers from the private sector into government "make piece of work" projects.[28] Regardless of their popularity or any other justifications for these proposals, the mammoth jump in economic growth that would be necessary to offset the furnishings of new debt is highly unlikely to materialize.

In fact, the sorts of public investments that are complementary to economic growth—such as improving or enhancing necessary infrastructure—would likely be squeezed out by the rising costs of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and new initiatives such as Medicare-for-All and free public college. States are already feeling the clasp on their educational and other spending to pay for their unfunded public pensions.[29] Overall, pro-growth investment spending is probable to be a prey—rather than a driver—of rising authorities debt.

Generational Fairness

Going securely into debt to fight World War Two, or fifty-fifty for major investments that will benefit current and hereafter generations, can be justified for their long-term benefits. Borrowing $103 trillion over the next iii decades to finance current consumption for seniors defies generational fairness. Fifty-fifty low interest-rate assumptions testify annual involvement payments rising to seven.6% of GDP (Figure 3) annually within a few decades. That represents the current equivalent of $1.seven trillion in almanac federal spending that will not be bachelor for future generations to safeguard national security, build infrastructure, brainwash children, or provide more targeted assistance to the poor. These big deficits and debt will leave trivial budgetary room to respond to deep recessions, national security crises, or other emergencies.

Generational equity tells usa that anything worth doing is worth paying for. If Washington wants to provide a total range of expensive services and benefits, it should be willing to fix priorities, cutting lower-priority spending, and raise the required tax acquirement. Only for legitimate long-term investments—and brusk-term crises—is at that place a strong upstanding or economic case for adding to futurity generations' debt burdens. Lawmakers should aim to minimize budget deficits over the course of the business bike.

Decision: Filibuster But Worsens the Inevitable Reforms

Current federal debt trends are unsustainable. Simply continuing current policies with small interest rates would produce a debt of nearly 200% (and growing) of the economy inside three decades—at which point, interest payments would swallow 42% of all federal revenue enhancement revenues. And this projection assumes no major wars, recessions, expensive new policies, or significant interest-charge per unit increases. Overall, CBO assumes lost income, less economic growth, and less policy flexibility for futurity generations.

In light of these factors, the near dangerous policy is to keep building debt and so await and encounter if a recession or financial crisis occurs. If it does, lawmakers will be forced to implement drastic fiscal consolidations at a time locked in their Social Security and Medicare benefits.

It would exist far more prudent for lawmakers to brainstorm reining in the $103 trillion Social Security and Medicare shortfall with gradual reforms.[30] Additionally, whatever new savings from spending restraint or tax increases should be applied to deficit reduction, rather than expensive new initiatives. This responsible fiscal stewardship would ensure a soft landing on deficits and strengthen the economic system for hereafter challenges.

Endnotes

Run into endnotes in PDF

Source: https://www.manhattan-institute.org/why-deficits-matter-to-the-us-economy

0 Response to "What Is Making Our Deficit So High Again"

Post a Comment